I have a very literary birthday. Virginia Woolf, Robert Burns, and Gloria Naylor make January 25th a day of which any writer can be proud. But Edith Wharton was born on January 24th and it kills me. My fellow New Yorker and dog lover, one of my favorite writers—off by a single day!

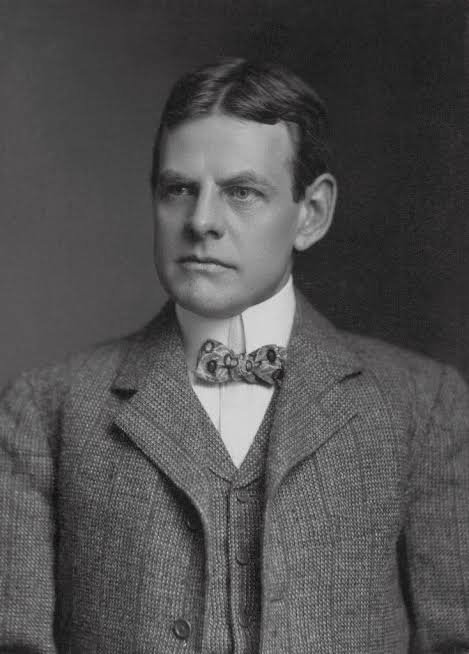

But the day that marks the birth of Edith Wharton marks the death of another writer, David Graham Phillips. In 1911, as she celebrated her 49th birthday, Phillips died after being shot six times outside the Princeton Club near Gramercy Park. Few people remember Phillips today, but at the time, he was considered “the leading American novelist”—by H.L. Mencken at least. Phillips came to national fame as a journalist with a series of essays later published as The Treason of the Senate, in which he accused several prominent senators of acting on behalf of a few wealthy families. An outraged Theodore Roosevelt dubbed him “the man with the muck rake,”—a title later shortened to muckraker—and so a legend was born.

In his novels, Phillips turned to the subject of the American woman; here he was equally scathing. As one character put it: “I have only one strong feeling and that is my contempt for women—the American woman.” Another observed, “You are of the new type—the woman that uses her brain. Give me the old-fashioned kind, that loved without question.” Women were doodlewits, parasites, noddleheads. He had a particular loathing for women who rode in cars, “drifting from one diversion to the next.”

A woman who uses her brain and loves motorcars immediately calls to mind Edith Wharton whose reputation as a novelist far surpasses that of Phillips today. But Mencken rejected Wharton as a candidate for the leading writer in America because like her friend and colleague Henry James, she was insufficiently “American.” One also suspects the fact that she was a woman disqualified her.

Mencken’s dismissal felt like a gauntlet. To choose an inferior writer with a marked contempt for women over a brilliant novelist whose work defines her era was an insult that demanded an answer. Wharton was not in New York when Phillips was killed; she was in Paris, working on Custom of the Country and Ethan Frome. But only three months earlier, she had been stranded in the city at the palatial Belmont Hotel, where she summoned Henry James, Walter Berry, and Morton Fullerton—master, oldest friend, and lover—to a dinner in which she sought their advice on whether or not to leave her husband, Teddy. In a very short time, she would upend her life entirely, leaving her husband, her publisher, and her country of birth. It’s the sort of dramatic coming into selfhood writers typically give to younger protagonists. But middle aged women break free and do bold things too.

Edith Wharton and David Graham Phillips. Two writers whose work depicted the strange and painful intersection of love and economics in the lives of women at the turn of the century—yet speak from such different points of view, I felt I had to put the two of them in conversation. So I took liberties with the timeline and delayed Mrs. Wharton a few months so she could encounter David Graham Phillips at the Belmont shortly before he is shot. In solving the mystery of his death and life, she finds her own way forward. The result is The Wharton Plot. I hope you enjoy.